My Kind of Smile!

Another MFA class begins, and once again I’m deep diving

into story structures. I have to admit, this is my kind of smile. And, it so

happens, I came across a new book that is my perfect cup of tea.

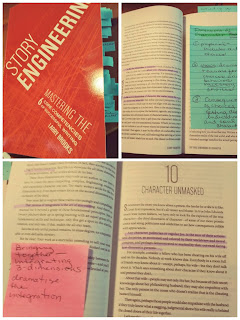

Considered “a master class in novel writing,” Story

Engineering, by Larry Brooks (Writer’s

Digest Books, 2011), takes a deep dive into story architecture. As Brooks

offers, “…in their execution, stories are every bit as engineering driven as

they are artistic in nature.” In other words, the technicality (or criticality)

of the story is as fundamental as the creative.

Exploring the ongoing debate of pantsing (otherwise called

organic writing) vs. plotting, Brooks offers that both strategies serve the

same function: to find the heart of the story, the one that begs to be told.

Pantsing tends to take the scenic route, going through revision after revision

(after revision) to eventually and hopefully find that essence of story. As

such, pantsing tends to be inefficient, as the writer stumbles through various drafts that too often miss the

mark. What if there was a way to

identify the core elements before you

dive into the deep end?

Brooks calls these

elements the six core competencies. Concept. Character. Theme. Story Structure.

Scene Execution. Voice. These are the

essential ingredients to a successful story.

Every creative cook understands that the “most delicious of

ingredients require blending and cooking – stirring, whipping, baking, boiling,

frying, and sometimes, marinating – before they qualify as edible…” It is the

delicious sum of these ingredients that turns your story into a “literary

feast.”

Story engineering is that recipe that brings these

ingredients together in a cohesive , satisfying dish. It differs from formulaic

writing in that the process of story engineering serves to bring clarity to

your story, but you bring the art. A pinch of this, a dash of that, stirred not

shaken, and you make the story your own.

Brooks’ detailed explorations into each of these

competencies decode the abstract. He provides a practical model that gives

writers a profound new understanding of story structure that is accessible, and

doable. One of my favorite passages in his definition of story:

“A story has many moods. It has good days and bad days. It

must be nurtured and cared for lest it deteriorate. And it has a personality

and an essence that defines how it is perceived. Just like human brings.”

As Books explains, a body cannot function without a heart.

So it is with stories. These certain competencies support the heart of the story. To continue with the

analogy of cooking, if an essential ingredient is missing, or soured, the

resulting dish leaves behind a bad taste.

Brooks is quick to admit that a writer can have all the

right ingredients, perfectly stirred, and it turns out bland. Or, to put it

another way, it’s possible to assemble in perfect order that perfect body. But

without that creative spark, there is no life. Think Frankenstein’s monster.

Now that we’re all hungry, I highly recommend this book.

May you create the perfect feast!

The Powers asked for a bio. I'm never good at these things.

Writer, middle grade fiction of various genres, featuring real kids with real

emotions dealing with real world issues. Armed with an MA in Children's

Literature (Simmons) and an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults

(VCFA), I have worked with childhood heroes, including the indomitable Marion

Zimmer Bradley (my first editor) and the genius that defines Gregory MacGuire,

Eric Kimmel and Marion Dane Bauer (all advisors); was a contributing writer to

Anita Silvey’s The Essential Guide to Children's Books and Their

Creators; a contributing writer to American Dissidents: An

Encyclopedia of Activists, Subversives ..., Volume 1.( Kathlyn Gay, editor.

Books include Big River’s Daughter (Historical Fantasy.

Holiday House, April 2013) Recommended by the International Reading

Association, the Historical Novel Society, and was nominated for the Amelia

Bloomer Project (American Library Association, 2013). The Girls of

Gettysburg (Historical Fiction. Holiday House, Fall 2014), a Hot Pick

on Children’s Book Council for September 2014, an honor for the 2015 Thomas

Jefferson Cup Overfloweth and an honor for the 2015 Paterson Prize for Books

for Young People. 'Nuf said.

While I understand the metrics-driven urge to characterize pantsing as inefficient, I am very wary of applying such concepts to creative processes. Efficiency requires waste, and labeling certain investments of time, effort, etc. as wasteful sets up a profound misunderstanding of creativity.

ReplyDeleteThis is not to say that creatives shouldn't regularly examine our processes to make sure they are meeting our creative needs. Using language and concepts based in mechanics and systems theory, though, may lead us to devalue the organic nature of creativity.

Hi Jennifer! I tend to think it’s more like poetry, right? A narrative has its own rhythm and timing, not much different that the metrics used in poetry, in which several elemental components (character, plot , conflict, theme and so on) are woven together in such a way that creates something that transcends the page. Something larger than life that also reveals our humanity. In fact, as often said, there is an underlying rhythm to every narrative -- both on the sentence level as well as the broader narrative --that impacts, unconsciously or not, the reader. As Brooks noted, one can have all the right ingredients, but without that spark – that creative spark – the story still lacks life.

DeleteI'm so fascinated by story structure / plotting techniques. I love trying out different plotting approaches with books--takes the sting out of the first draft!

ReplyDeleteI do, too, Holly! In the end, of course, a writer composes their own process, what works for them. What I liked about this book was his deep-diving into each of these “ingredients”, offering connections that serve to deepen the meaning of the story to keep the reader engaged.

Delete