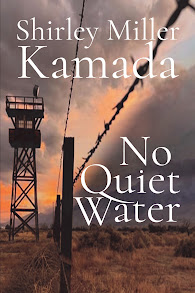

Interview with Shirley Miller Kamada, author of No Quiet Water

1. I always start with the most obvious request: Please give us a one-sentence synopsis for No Quiet Water.

No Quiet Water is a coming-of-age story about a

10-year-old Japanese American boy, Fumio, who is forced into an internment camp

with his family during WWII, and his loyal dog, Flyer, who was left behind.

2.

Please tell us a bit about the real-life inspiration behind No Quiet Water.

Two

years after I married my husband, Jimmy Kamada, I learned of his family’s World

War II internment experience. They were incarcerated first in Puyallup at Camp

Harmony, and then in Idaho’s Camp Minidoka. His parents were born in Seattle.

They were citizens. Realizing I knew nearly nothing about the internment, I began

my research. Much of what I learned I felt I should share.

To

inspire in a reader a visual image is an effective way to convey the true nature

of a situation. “What happened? How did that look?” My hope is to gently urge

the[JKaSM1] reader to ask, “And how did that feel?”

3.

I was pleasantly surprised by the first chapter from Flyer’s POV. What brought

you to telling the story (at least in part) from the eyes of the farm dog?

When No Quiet Water

was still a pup of a story, I was invited to visit Rockin’ Bar Border Collies,

where Rod and Debbie Goodwin raise and train these super-intelligent

animals. I knew that a border collie—Flyer—must be a primary voice. Flyer, rescued as a pup by Fumio’s grandfather,

remained with family friends, the Whitlocks, on Bainbridge Island when the

Miyotas were forced to leave.

Border collies are not

fighters. It is their nature to "gather together” not only sheep, but

ducks and geese and, sometimes, children. Even young dogs have a keen sense of

who to trust, and those trusted by a dog feel favored. Border collies are

intensely loyal.

Those who would like to know more about border collies [PC2] [JKaSM3] will

find an article and a video from “On the Lamb Herding” on my website.

Is a Border Collie

the Pet for You? | Shirley Miller Kamada

4.

Please tell us a bit about the level of distrust / suspicion of espionage regarding

Japanese Americans during this time, and how that shows up in the book.

One of the quotes that resonated with me was when Fumio thinks,

simply, “It’s our war.” And yet, they were treated as enemies in their own

country. Can you speak to this a bit–how it resonates through the book and your

conversations with those who remember the internment camps?

At ten years of age—the very age at which, in my teaching days, classroom Social Studies lessons centered on United States history—Fumio understood that he and his family had been targeted and betrayed by their own country. Community leaders of Japanese heritage were quickly taken into custody after the bombing of the fleet in Pearl Harbor. Records show that the government had, for decades, tracked Japanese Americans who had any sort of influence.

In No Quiet Water, Fumio’s friend Joey’s father was taken

from the family home and consigned to a Justice Department camp because he was

president of the island’s Farmers Association, despite that he had promoted

raising additional crops to help the Allied war effort.

Fumio would have known that Japanese Americans already serving in

the military had been reassigned to lower-level duties. Soon, Japanese

Americans would not be accepted for military service. Finally, they were

drafted and those who did not report were jailed.

I am interested in the question, “How does this resonate in

conversations with those who remember the internment?” but I cannot answer it

directly. Those who were adults in camp locked the memories in compartments

they seldom opened. My husband has said the camps were not discussed even among

family. There was a silent agreement: Let the past be the past.

5.

One of the most inspiring parts of the book is the attempt to find or make

beauty even in such difficult times. Why did you choose drumming specifically?

Visiting Japan to see relatives, Jimmy and I were thrilled to find that KODO, a world-renowned taiko group, was performing near our hotel. The taiko drummers were friendly. Youngsters in the audience were encouraged to try instruments. The performance was uplifting. The drumbeat became the heartbeat of those gathered.

Intrigued, I found Heidi Varian’s authoritative book, The Way

of Taiko.

Taiko drumming is over a thousand years old. Author Heidi Varian

has written, “The taiko drum makes so powerful a sound that in ancient times it

was said the boundaries of a Japanese village were determined by how far the

sound of the village drum carried. … The taiko symbolized community.”

My inclusion of ensemble taiko drumming was an artistic

decision. In the 1940s, the drums accompanied Obon ceremonies, and they were

used to provide rhythm for the study of martial arts. Ensemble taiko

performances are cited as having appeared in 1951. My belief is that growth

toward ensemble performance began earlier, and Fumio would have found the dojo

both a haven and a place of growth.

6. I thought it was interesting that there were such different

ideas about what needed to be done: those who only wanted to do what was asked, those who wanted peaceful protests (writing to

government officials, contributing editorials, working to prove good citizens),

and those who wanted their resistance to be seen.

I’m glad to address this question! This is a key consideration

in our understanding of the actions of Japanese Americans living in the military

zones of the western United States.

Younger generations, especially, ask, “Why didn’t Japanese

Americans protest? Why didn’t they push back?” It’s important to know that they

did protest, but not in ways we might identify as such today.

Those who were to be interned had few options. Strict curfews

were put in place and travel was disallowed. Bank accounts were frozen. For a

brief time, they were given the choice to move out of military zones, but permission

was rescinded abruptly, and only a very small number were able to do so.

A priority for most Japanese Americans was the health and safety

of their families. They felt that the most effective way to prove themselves

“good Americans” was to live as Americans, to demonstrate American values, trusting

that the government had their best interests at heart. Prejudice, though, was

rampant and was turned to profit-making by those who chose to leverage it,

building barracks and installing facilities to isolate Japanese living in the

country legally and, also, United States citizens.

As one form of resistance, letter writing campaigns were

launched, notably by women such as Mothers of Minidoka, urging that their sons

not be drafted from internment to the military, but to first acknowledge their

rights as citizens and free them and their families.

Nina Wallace, with Densho, The Legacy Project, writes, “The

First Lady was the only person to respond to the Mothers’ Society of Minidoka

petition in a hurried letter dictated to a secretary because ‘Mrs. Roosevelt

had to leave before signing.’” Responses to letters of petition from other

women’s organizations “ranged from curt

to patronizing to vaguely threatening,” such as one from Dillon Myer that “simultaneously

thanked the mothers for their ‘devotion… to the democratic principles’ and

warned them against ‘indicating reluctance to contribute to the winning of the

war.’” Imagine, this in response to a letter.

An example of perhaps more active resistance, regarding

conditions at Camp Minidoka: On January 6, 1944, seventy-five Issei and Nisei

women marched on the offices of Assistant Project Director R.S. Davidson and

held an eight-hour sit-in, demanding that camp administrators meet with

striking boilermen and janitors and restore hot water to the camp. This effort

by the women met with success.

The protests of the 1960s were more publicly visible. Yuri Kochiyama took inspiration from Malcolm X whom she met

in October 1963. Her subsequent activism was admittedly controversial. We see

in it, though, how resistance to human rights violations changed in later

years.

7. Where will your

writing take you next?

I have begun a novella in which Fumio’s

best friend Zachary Whitlock will, in his own words, tell about his experiences

as a youth on Bainbridge Island during World War II. Zachary’s family belonged

to the Friends Church, a Peace Church. I am drawn to delve into his

perspective. I want, also, to follow his path to adulthood and consider how his

early experiences influenced his later life.

# # #

Related to Question 3: Rockin’ Bar Border Collies, Rod

and Debbie Goodwin,

https://rockinbarbordercollies.com/

Related

to Question 5: The Way of Taiko, Heidi Varian, Stonebridge Press, Second Edition, 2013.

Related to Question 6: A Brief History of

Japanese American Relocation During World War II (U.S. National Park Service)

(nps.gov)

and

Comments

Post a Comment