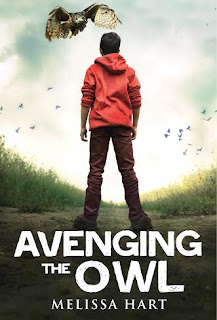

INTERVIEW WITH MELISSA HART, AUTHOR OF AVENGING THE OWL

I'm utterly delighted to share a recent conversation I had with Melissa Hart, author of AVENGING THE OWL--a fantastic book young readers will absolutely devour:

1. AVENGING THE OWL has so many attention-grabbing

aspects: the environment, dealing with life changes, Down syndrome, mental

health issues, not to mention the STAR WARS connection. What piece came to you

first? How did the book originate?

It is pretty multifaceted, isn’t it! I volunteered at my

local raptor rehabilitation center for eight years. During that time, a teen

boy began volunteering on my shift. He’d apparently left his mandatory high

school service hours until the last minute and could only complete them at the

raptor center—all the other “good” non-profits had been taken. He came in

despising birds, terrified of them. For several weeks, he struck me as sullen

and resentful, completely unengaged. But he fell in love with the raven that

lived at the center, and began learning about how smart these birds are. He

spent more and more time teaching himself about ravens and how to provide

enrichment for them when they’re living in a mew. Gradually, his enthusiasm

extended to the raptors. He ended up a guest at my wedding (also at the raptor

center) and gave me a beautiful sketch he’d done of me and an owl. I found his

emotional transition to be absolutely fascinating, and I wanted to explore it

in a novel.

2. I found myself gaining knowledge while being

propelled by your characters. How much research was involved? What was your

research made up of—library work or real-life experiences? How much time did

you spend on research compared to writing?

I researched on the job, so to speak. As a volunteer raptor

rehabilitator and educator, I spent eight years immersed in the world of owls,

hawks, falcons, eagles, etc. My research for this book is made up of real-life

experience, and I checked facts with my husband, Jonathan, who started

volunteering at the raptor center the year before I did. As far as Eric’s

character goes, my younger brother is a person with Down syndrome, and I grew

up helping to care for him. I also worked for a few years as a special

education teacher, and some of my students were people with Down syndrome.

3. I’m a SW Missouri native, and find myself often

writing about my own area of the country—are you native to Oregon? How does

living in your own area of the country shape your writing?

I’m actually not native to Oregon. I grew up very close to

where Solo spends his childhood—he’s in Redondo Beach, and I grew up in

Hawthorne (about six miles away) and in Oxnard, California on the beach. Like

Solo, I missed the warm ocean and the constant sun when I moved up to Oregon 15

years ago. And like Solo, after I got over my initial shock at my adopted

state’s rain and cold winters, I fell in love with the flora and fauna and the

uncrowded beaches and forests and deserts. This love definitely shaped my

descriptions of Solo as he begins to notice the trees and birds and lichen

around him.

4. Can we expect another MG read set in these

surroundings?

Most definitely. I’m finishing up a YA novel set in Costa

Rica, and after that, I’m planning a middle-grade novel set again in Oregon. It

may be a little more urban, but even our urban areas—at least in my hometown of

Eugene—can get a little wild!

5. You’ve taught literature and writing for a wide

variety of age groups and in a wide variety of formats (K-12, college,

distance-learning, etc.) How has teaching shaped you as an author?

Teaching the subject of creative writing has improved my own

writing one hundred percent. Most of the classes and workshops I’ve taught over

the past 20 years involve a great deal of reading, and literary analysis.

(You’ve got to do all the homework as the teacher, too—not just as a student!)

I’ve found that when I’m analyzing a book or an essay or a short story in order

to teach it to a class, I get a much better sense of how the author’s put the

narrative together with respect to plot and characterization and other

elements. I find that when I’m teaching narrative nonfiction, I get inspired to

write more essays. Likewise, when I’m teaching creative writing to high school

students, I’m excited to delve into fiction for middle-grade and young adult

readers. Right now, I’m teaching a general nonfiction class to Master of Fine

Art students for Northwest Institute of Literary Arts in Washington; the

reading and writing assignments have inspired me to play with new forms such as

flash-nonfiction (750 words or fewer) and essays inspired by pop culture such

as the TV show with which I grew up—Land

of the Lost.

Solo learns many lessons, not the least of which occurs when

he releases the owl and realizes his anger has become a memory. Is this a

lesson you were especially interested in sharing with your own students? Do you

often find yourself incorporating life lessons into your writing that you wish

you could share with your younger students?

I didn’t consciously put that lesson into the book to teach

readers anything. I’ve studied a lot of Buddhist philosophy, mostly in the form

of books and audio from Jack Kornfield of Spirit Rock Meditation Center, and some

of these lessons come directly from Buddhist teachings. I haven’t mastered any

of them. This idea of releasing anger is a skillful one, to be sure, and I have

to relearn it over and over. Mostly, I deal with anger by going for a long run.

But releasing an owl, or otherwise immersing oneself in a hobby or passion, is

a wonderful distraction from anger. It’s important, though, to own your anger,

as well. The Buddhists like to quote poet William Blake, saying, “The tygers of

wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction.” I think that means that

sometimes, instead of trying to rationalize our anger, we just need to immerse

ourselves in it—kind of like Lewis Black’s Anger character in the film, Inside Out. Now that dude owns his anger!

6. Solo’s friendship with Eric is compelling and

again a heart-warming learning experience. Your author bio indicates you have a

brother with Down syndrome. Did any of your own life experiences with your

brother become part of AVENGING THE OWL?

I grew up feeling the tension between my brother and father.

Some of this tension informs Eric’s relationship with his own father in the

novel. While specific anecdotes didn’t make it into the book, the scenes with

Eric are informed by my brother’s sweet temperament—particularly as a kid

Eric’s age, he had such a kind heart, and he was absolutely hilarious . . .

intentionally. He loved making people laugh. Unlike Eric, my brother doesn’t

like to hike, and doesn’t particularly care about insects or nature. He’s much

more interested in the Los Angeles Lakers and hanging out with his girlfriend,

a woman with Down syndrome.

7. I’m especially fond of the passage late in the

book in which Solo realizes that “people hate what they don’t understand.” It’

s a lesson we all need to be reminded of right now. Was there a time in your

own life that you needed to be reminded as well?

Good question. I admit, I’m not overly fond of the people

who took over the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in January. I’ve been there

several times with my family, and it’s a lovely, special place for people who

just want to immerse themselves in the natural world. I resent the fact that

this group with their guns and intimidating appearances kept bird-lovers and

others from getting to explore this area of Eastern Oregon. Their actions also

made life difficult for the Refuge’s employees and volunteers, and other

demographics such as kids just trying to get to school. While I won’t say I

hate the people who took over the Refuge, Solo reminds me that I need to

educate myself more fully about their perspective on the land rights issue and

at least attempt to understand their anger.

I was intrigued by the way you incorporated screenplay-style

writing. Is this only because Solo writes screenplays? Or do you find that

young readers “see” books playing out in their minds like movies?

I hadn’t the faintest idea how to write a screenplay scene

before I wrote Avenging the Owl. But

Solo’s father works in Hollywood, and it felt natural for Solo to take a

screenwriting course so close to that city. Screenwriter Cynthia Whitcomb up in

Portland, Oregon, has been teaching incredibly successful screenwriting classes

for years; several of my friends have taken them and talked about all that

they’ve learned, so screenwriting’s been on my mind. I think most readers—young

and old—see novels as playing out in their minds like movies. The trick as an

author is to help them imagine each scene as vividly as possible so that

they’ll keep reading instead of turning on the TV!

8. How about you—is there a screenplay in your own

future? If not, what can we expect to see from you next?

I don’t have plans to write a screenplay. As soon as I’m

finished with the YA novel and the new MG novel, I’m hoping to sit down and

write a historical novel based on the lives of my great-grandparents who ran

away separately as teenagers to join the circus, where they met and married

even though they didn’t get along. I can’t tell yet whether it wants to be a

book for children, for adults, or for both. Come to think of it, I could learn

a thing or two from Solo--maybe it should be a screenplay!

~

Keep up with Melissa -

~

Keep up with Melissa -

Website: www.melissahart.com

Instagram: WildMelissaHart

Comments

Post a Comment