On the Fearlessness of Her Story

As we continue to explore the adventurous and fearlessness,

I’ve long written about the heroine’s journey. In fact, both of my MGs – the historical

fantasy Big River’s Daughter (Holiday House

2013), and the historical fiction, Girls of Gettysburg (Holiday House, 2014)—have

explored plot movements of the heroine’s journey.

The protagonist of any story, the hero if you will, acts as

a window inviting the reader into the story. The reader is drawn into the

narrative because, just as the protagonist searches for their identity, the

reader is engaged in their own search. Yet, if the hero is always male, and the

journey is always his story, what recourse is left to young adult

women and adolescent girls? What is her story? (An obvious question

becomes, with the current movement toward LGBTQ representation, what is their hero’s

journey? This discussion doesn’t address the specifics in the LGBTQ journey for identity, but hopefully someone

more informed than I am will take up that call of action!)

The profound truth, and primary function, of adolescence is the separation from

parent, the search for uniqueness and the triumphant integration into

wholeness. It’s the essence of the archetypal hero’s journey. Every child looks

for their own hero to identify with. Every reader seeks guides – protagonists –

to show them how to begin their journey.

But that doesn’t mean their journey is the same. Even if the heroine’s journey

follows a similar path, toward a similar purpose, there is a difference

between his journey and her journey. (And by extension,

their journey.)

Megan Leigh (Dispelling the Myth of Strong Female Characters) offers

interesting insight into the “myth” of strong female characters. Among many

stories (and movies) claiming to have strong female characters, one overriding

issue seems to be distinguishing between strong and weak, and passive and

active characters. A female who is caring, vulnerable, even emotional tends to

be considered a weak character. Yet, a strong female who is aggressive,

abrasive, even with difficulty connecting emotionally, is considered negative.

Both types are flat, negating their own flawed, complex humanity. As such, both

types are reduced to a stereotype. In contrast, male characters are often

allowed to play the full emotive spectrum. Says Leigh, in too many stories, the

strong female protagonist is considered “special,” the exception or chosen

one. If only one woman is ever shown to be capable and complex, and is

presented as the exception, the “very framing of the narrative in a way that

has men writing off most females as incapable, is an issue unto itself.”

Tasha Robinson (We’re Losing All Our Strong Characters to Trinity Syndrome)

considers Valka, the long lost mother of Hiccup in the movie How To Train

Your Dragon 2. Valka is complicated, formidable, wise and damaged, and she

is fully capable of taking care of herself. For decades she had successfully

avoided capture and death at the hands of the bad guys. Yet, within minutes of

coming onto the scene, she becomes suddenly inadequate and needs to be rescued

– twice. And for the rest of the film, she does nothing except tell

Hiccup that he is the chosen one. She has become superfluous.

Recently Harold Underdown (Executive Editor of Kane Press and owner of the website,

Purple Crayon) recommended several books on his Facebook page (which he does

every Friday. Check out his Facebook page, for his recommendations are terrific!).

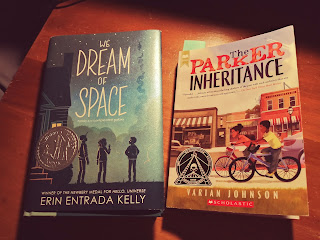

The Dream of Space, by Erin Entrada Kelly (Greenwillow

Books, 2020) presents a trio of protagonists, brothers Cash and Fitch, and

sister Bird. Bird is my favorite for all the reasons noted above. She dreams of

becoming NASA’s first female shuttle commander, but her ordeals include

verbally abusive, even negligent parents, her wayward brothers, and a slew of misadventures

in school. Her journey is set against the backdrop of the Challenger

Shuttle disaster. The book is a great study in creating multidimensional

characters that engage readers on the deepest, gut-wrenching level. It also

illustrates the differences between narration (exposition/telling) and

dramatization (showing).

Another recommendation is Varian Johnson’s The Parker Inheritance

(Scholastic, 2018). A puzzle mystery, this is an intriguing study in viewpoint and

the power of perception. Following her parent’s divorce, twelve-year old

Candice and her mother move into her deceased grandmother’s house in Lambert,

South Carolina. Struggling with her parent’s divorce, as well as the threat of

poverty, Candice finds a mysterious letter addressed to her grandmother. The

letter describes the Washington family, who were run out of Lambert during the

turbulent 1950s. It also promises a fortune to anyone who can figure out the

clues. The letter is her call to action. As she and her new friend Brandon decipher

the clues, they discover not only the terrible secrets of the town haunted by

its racially divided past, and the sad truth

behind her grandmother’s destroyed

reputation, they experience several instances of racism. This serves to

motivate them all the more to find justice for the Washington family and her

grandmother. Many chapters are told from the POV of other characters who lived

in Lambert during the 1950s.

Returning to the mother of Hiccup, Valka. As an ancient

symbol, the dragon (according to Jung) is “the wildness of spirit,” which

escapes and destroys the artificial order of oppression. Valka, however, had

her wings metaphorically clipped just as she was becoming interesting. How many

characters have we followed that, in the end, have their wings clipped?

Both Bird and Candice remain fearless and engaging in their

search for personal truth. In my own characters,

I continue to explore the language, the ordeals and symbols that are uniquely her own, focusing on a fearless protagonist with her

own identity, agenda and story purpose.

Who are your favorite strong female protagonists?

--Bobbi Miller

GREAT recommendations--and what a great discussion of archetypes.

ReplyDelete